Shashin-an

写真庵2022 - in progress.

Shizuoka prefecture, Japan.

With support from Thomas Vauthier, Yoann Moreau, and people from Okubo.

写真庵は、長期にわたる時間軸と多様な展開を持つリサーチ・クリエーションプロジェクトであり、2021年から継続している。茶室であると同時にカメラ・オブスクラの装置でもある小屋の構想から建設、さらに茶会を通じた起動に至るまで、その発展は、それが生まれる環境の中で、またその環境を通じた観察として位置づけられる。

写真庵は観察装置の歴史に位置づけられると同時に、その名称自体もそれを示唆している。「写真」は「現実の写し(コピー)」を意味し、また「庵」は日本の茶室の伝統や、中国における世紀からの隠者の庵(庵=庵、庵室)を指す。写真庵の建築形式とその場所、すなわちパーマカルチャー農園の一角にあるという立地は、日本の田舎に見られる菜園小屋を想起させる。そのような小屋には、茶室に通じる「無常」や「簡素さ」の理想が色濃く現れている。

写真庵の構想と建設の過程は、2021年11月から2023年11月までの9回にわたる現地滞在を通じて行われた。そこでは、既にそこにあるものとの協働(「既にあるもの」との共作)という姿勢が重要となる。これは大竹伸朗の芸術実践に通じるものであり、彼は「良い素材」を見つけるためには、良い人に出会うことが必要だと述べている。写真庵に使用された材料はすべて、その場所との関係性の中で得られたものであり、交換、贈与、散策、地域の語りといったプロセスの中で集められた。さらに、地元の職人や大工(プロ・アマ問わず)からの助言や手助けによって、素材の集積だけでなく、その組み立てそのものが環境を「ネガのように」浮かび上がらせるものとなっている。

このように、素材やその実装の仕方は、環境との協働、すなわち「ともに働くこと」の産物であり、それは茶室建築にまつわる伝統的な技術から、アマチュア大工によるDIY的技術までを含む。

このプロセスは、生き物の織りなす関係のネットワークを明らかにするだけでなく、それ自体がひとつのオーサーシップの力、あるいは環境の物質的ドキュメントとも言える。なぜなら、写真庵の大きさ、色、素材などの選択は、私たち人間の意思だけで決めたものではなく、それら素材の入手可能性や、もっと言えば「環境そのもの」もまた決定に関わったからである。写真庵の建築は、地域に根差した具体的な「環境のイメージ」を形成し、そこには竹林(植物的次元)、土(地質的次元)、富士山の観察をめぐる住民の語り(感情的次元)、そして茶会のために貸与・寄贈された道具(象徴的次元)など、さまざまな側面が重なっている。それはまさに「エコ=テクノ=シンボリックな関係性」を可視化する「メソグラム」である。

特に、正人さんからの贈り物により、カメラ・オブスクラのアイデアが明確になった。彼が使用しなくなったYashicaをファニーに譲渡したことで、大久保の風景を上下反転して見ることができるようになり、この装置のアイデアが抽象的ではなく、「環境の中から」生まれたことが確信された。風景の像を反転し、環境を具体的に出現させることは、操作的な変容であり、写真庵での茶会はその操作的な変容と連動している。カメラ・オブスクラの核心的特徴である「像の反転」は、慎ましく、少ない手段で成し遂げられる点も含めて、写真庵のあり方と響き合っている。

したがって、写真庵は、環境を「表現する」のではなく(それはまだ人間中心的な態度である)、環境に「印象させる」装置であり、三層の印象が現れる:

EN

Shashin-an 写真庵 is a long-term research-creation project initiated in 2021, characterized by multiple temporalities and deployments. It involves the conception and construction of a tea hut that also functions as a camera obscura. The process includes extended stays on-site, collaboration with local residents, and the use of donated or repurposed materials. The aim is to observe and reveal the surrounding environment through architecture, materials, and tea ceremonies.

Shashin-an 写真庵 is a long-term research-creation project with multiple temporalities and phases of development, ongoing since 2021. From the design to the construction of a tea hut that also functions as a camera obscura, to its activation through tea gatherings, the project unfolds as an observation of the milieu in which—and through which—it comes into being.

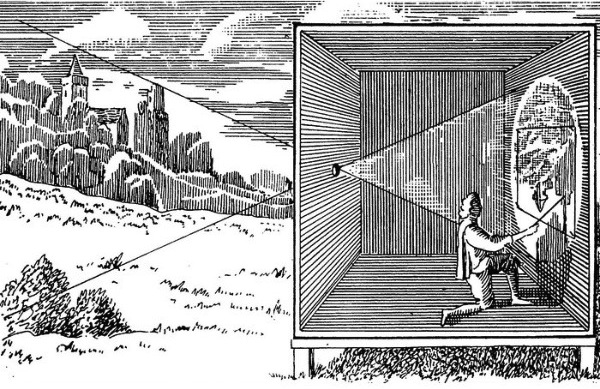

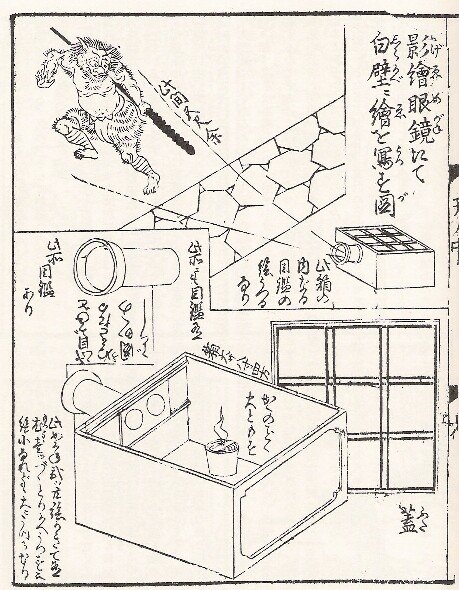

Shashin-an belongs to the lineage of observational devices, and its name is indicative of this: shashin means photography, or a "copy of reality" (写真), while the suffix -an evokes the tradition of Japanese tea pavilions as well as Chinese hermit huts (iori) from as early as the 4th century. Both the form of the building and its location—set within a permaculture vegetable garden—recall the koya, or garden shed, typical of Japan’s rural landscapes (inaka), whose ideals of impermanence (mujō) and frugality echo those of the tea pavilion.

The design and construction process of Shashin-an spanned nine on-site stays between November 2021 and November 2023. Central to this process was a commitment to “cooperating with what is already there”—an approach akin to that of artist Otake Shinro, who says that to find “the right junk,” one must first encounter the right people. All materials used in the construction were gathered through relational processes—exchange, gift, walks, local stories—emphasizing a direct engagement with the milieu. The structure was assembled with the help and advice of both professional and amateur local carpenters (daiku), making the act of building itself a way to bring the milieu to light, like a photographic negative.

The methods of collecting and assembling materials thus express a collaborative practice—not only with people and techniques (from traditional tea architecture to vernacular DIY carpentry), but with the milieu itself. This approach reveals the network of the living, inscribed in matter and relationship, and asserts a form of authorship—or even a material documentary—of the milieu. The choices of size, color, and material were not made by humans alone: the availability of materials—and more precisely, the milieu—also decided.

The resulting architecture offers a concrete image of its environment, reflecting many of its dimensions: vegetal (bamboo from nearby woods), geological (clay from the carpenter’s land and the garden), affective (stories about watching Mt. Fuji, objects lent or gifted for ceremonies). It creates what might be called a mesogram, revealing the milieu’s eco-techno-symbolic relations.

A turning point came with a gift from Masahito: a Yashica 6x6 camera he no longer used, which he gave to Fanny. Through this, the idea of the camera obscura solidified—not as a theoretical projection, but rooted in the place. Inverting the landscape’s image became a way to manifest the milieu concretely. In Shashin-an, tea gatherings participate in the same operational logic as the camera obscura: to produce a reversed, modestly made image. The point was to overturn familiar ways of seeing, grounding, and orientation—in short, to challenge the obvious. Reversal evokes subversion, even revolution: one overturns a regime or a king—here, the POMC, or the classical modern Western paradigm.

Thus, Shashin-an is not a device for expressing the milieu (which would still be anthropocentric), but for imprinting it, revealing three levels of impression:

写真庵は観察装置の歴史に位置づけられると同時に、その名称自体もそれを示唆している。「写真」は「現実の写し(コピー)」を意味し、また「庵」は日本の茶室の伝統や、中国における世紀からの隠者の庵(庵=庵、庵室)を指す。写真庵の建築形式とその場所、すなわちパーマカルチャー農園の一角にあるという立地は、日本の田舎に見られる菜園小屋を想起させる。そのような小屋には、茶室に通じる「無常」や「簡素さ」の理想が色濃く現れている。

写真庵の構想と建設の過程は、2021年11月から2023年11月までの9回にわたる現地滞在を通じて行われた。そこでは、既にそこにあるものとの協働(「既にあるもの」との共作)という姿勢が重要となる。これは大竹伸朗の芸術実践に通じるものであり、彼は「良い素材」を見つけるためには、良い人に出会うことが必要だと述べている。写真庵に使用された材料はすべて、その場所との関係性の中で得られたものであり、交換、贈与、散策、地域の語りといったプロセスの中で集められた。さらに、地元の職人や大工(プロ・アマ問わず)からの助言や手助けによって、素材の集積だけでなく、その組み立てそのものが環境を「ネガのように」浮かび上がらせるものとなっている。

このように、素材やその実装の仕方は、環境との協働、すなわち「ともに働くこと」の産物であり、それは茶室建築にまつわる伝統的な技術から、アマチュア大工によるDIY的技術までを含む。

このプロセスは、生き物の織りなす関係のネットワークを明らかにするだけでなく、それ自体がひとつのオーサーシップの力、あるいは環境の物質的ドキュメントとも言える。なぜなら、写真庵の大きさ、色、素材などの選択は、私たち人間の意思だけで決めたものではなく、それら素材の入手可能性や、もっと言えば「環境そのもの」もまた決定に関わったからである。写真庵の建築は、地域に根差した具体的な「環境のイメージ」を形成し、そこには竹林(植物的次元)、土(地質的次元)、富士山の観察をめぐる住民の語り(感情的次元)、そして茶会のために貸与・寄贈された道具(象徴的次元)など、さまざまな側面が重なっている。それはまさに「エコ=テクノ=シンボリックな関係性」を可視化する「メソグラム」である。

特に、正人さんからの贈り物により、カメラ・オブスクラのアイデアが明確になった。彼が使用しなくなったYashicaをファニーに譲渡したことで、大久保の風景を上下反転して見ることができるようになり、この装置のアイデアが抽象的ではなく、「環境の中から」生まれたことが確信された。風景の像を反転し、環境を具体的に出現させることは、操作的な変容であり、写真庵での茶会はその操作的な変容と連動している。カメラ・オブスクラの核心的特徴である「像の反転」は、慎ましく、少ない手段で成し遂げられる点も含めて、写真庵のあり方と響き合っている。

したがって、写真庵は、環境を「表現する」のではなく(それはまだ人間中心的な態度である)、環境に「印象させる」装置であり、三層の印象が現れる:

- 材料とその存在感による現れ:木材のような物質的な素材に加え、技術や感情、村人の願い、出会い、友情、そして収集・貸与・寄贈された道具といった一見非物質的なものも含まれる。

- 茶の物語的なパフォーマティヴィティ:茶道具拝見では、従来の形式に従わず、地域で得られた素材や道具、そしてそれを通じて見える地域性について語ることができ、環境を「反転」して現出させる。

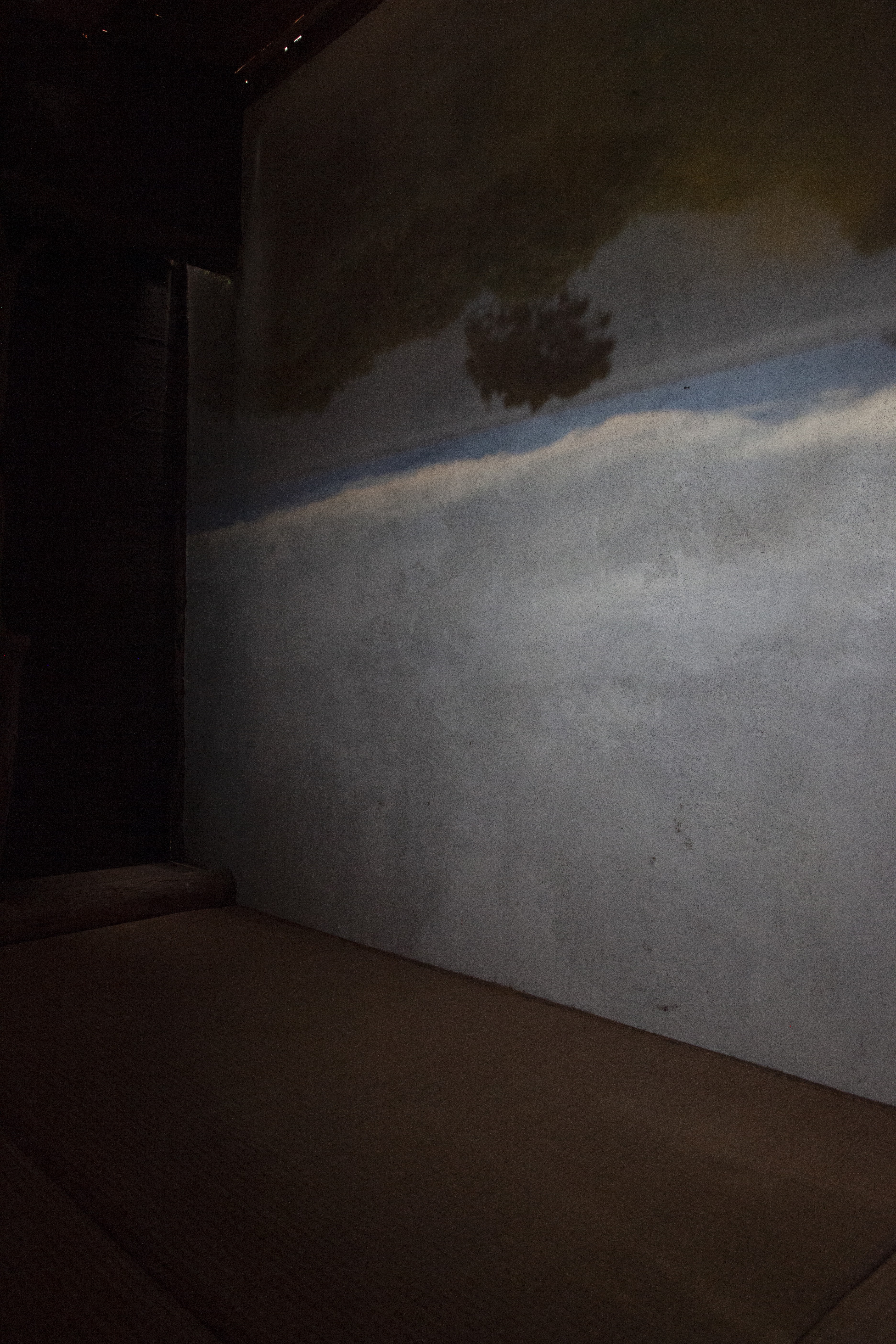

- 装置としての写真庵がもたらす視線の反転:カメラ・オブスクラのドラマトゥルギーによって、遠くの風景が小屋の内部に現れ、訪問者と同じ空間、同じ「肉体性」において共鳴する。身体の影が即座に像に焼きつき、視線は不安定さの中で新たな「掴みどころ」を得て、反転された像にしがみつく。茶会もまた、貧しいものや拾得物を「見立て」の手法で用いることにより、ある種の視覚の革命を担う。

EN

Shashin-an 写真庵 is a long-term research-creation project initiated in 2021, characterized by multiple temporalities and deployments. It involves the conception and construction of a tea hut that also functions as a camera obscura. The process includes extended stays on-site, collaboration with local residents, and the use of donated or repurposed materials. The aim is to observe and reveal the surrounding environment through architecture, materials, and tea ceremonies.

Shashin-an 写真庵 is a long-term research-creation project with multiple temporalities and phases of development, ongoing since 2021. From the design to the construction of a tea hut that also functions as a camera obscura, to its activation through tea gatherings, the project unfolds as an observation of the milieu in which—and through which—it comes into being.

Shashin-an belongs to the lineage of observational devices, and its name is indicative of this: shashin means photography, or a "copy of reality" (写真), while the suffix -an evokes the tradition of Japanese tea pavilions as well as Chinese hermit huts (iori) from as early as the 4th century. Both the form of the building and its location—set within a permaculture vegetable garden—recall the koya, or garden shed, typical of Japan’s rural landscapes (inaka), whose ideals of impermanence (mujō) and frugality echo those of the tea pavilion.

The design and construction process of Shashin-an spanned nine on-site stays between November 2021 and November 2023. Central to this process was a commitment to “cooperating with what is already there”—an approach akin to that of artist Otake Shinro, who says that to find “the right junk,” one must first encounter the right people. All materials used in the construction were gathered through relational processes—exchange, gift, walks, local stories—emphasizing a direct engagement with the milieu. The structure was assembled with the help and advice of both professional and amateur local carpenters (daiku), making the act of building itself a way to bring the milieu to light, like a photographic negative.

The methods of collecting and assembling materials thus express a collaborative practice—not only with people and techniques (from traditional tea architecture to vernacular DIY carpentry), but with the milieu itself. This approach reveals the network of the living, inscribed in matter and relationship, and asserts a form of authorship—or even a material documentary—of the milieu. The choices of size, color, and material were not made by humans alone: the availability of materials—and more precisely, the milieu—also decided.

The resulting architecture offers a concrete image of its environment, reflecting many of its dimensions: vegetal (bamboo from nearby woods), geological (clay from the carpenter’s land and the garden), affective (stories about watching Mt. Fuji, objects lent or gifted for ceremonies). It creates what might be called a mesogram, revealing the milieu’s eco-techno-symbolic relations.

A turning point came with a gift from Masahito: a Yashica 6x6 camera he no longer used, which he gave to Fanny. Through this, the idea of the camera obscura solidified—not as a theoretical projection, but rooted in the place. Inverting the landscape’s image became a way to manifest the milieu concretely. In Shashin-an, tea gatherings participate in the same operational logic as the camera obscura: to produce a reversed, modestly made image. The point was to overturn familiar ways of seeing, grounding, and orientation—in short, to challenge the obvious. Reversal evokes subversion, even revolution: one overturns a regime or a king—here, the POMC, or the classical modern Western paradigm.

Thus, Shashin-an is not a device for expressing the milieu (which would still be anthropocentric), but for imprinting it, revealing three levels of impression:

- Through the presence of materials forming an image: not only tangible elements like wood, but also intangible ones—knowledge, affect, the villagers’ desires, their encounters and friendships, as well as objects gathered, borrowed, or gifted by the milieu.

- Through narrative performativity in tea gatherings: during chadōgu no haiken (presentation of tea tools), instead of describing conventional implements, Shashin-an allows for storytelling about and through locally gathered materials and objects, making the milieu appear in reverse. These privileged dialogical moments—unique to chakai—are also the basis for documentary recordings of a fragile community.

- Through the reversal of vision enabled by the Shashin-an device: the camera obscura and its dramaturgy allow a distant landscape to emerge inside the hut, occupying the same space and corporeality as the guests. Shadows of bodies imprint themselves instantly onto the shared image. The viewer, momentarily disoriented, finds new anchors in the milieu—clinging to the inverted, revolutionized image. The tea gathering also subverts norms by employing humble or repurposed objects through mitate, a gesture of visual transformation.

Shashin-an (montage loopé), 2024, 45 minutes